|

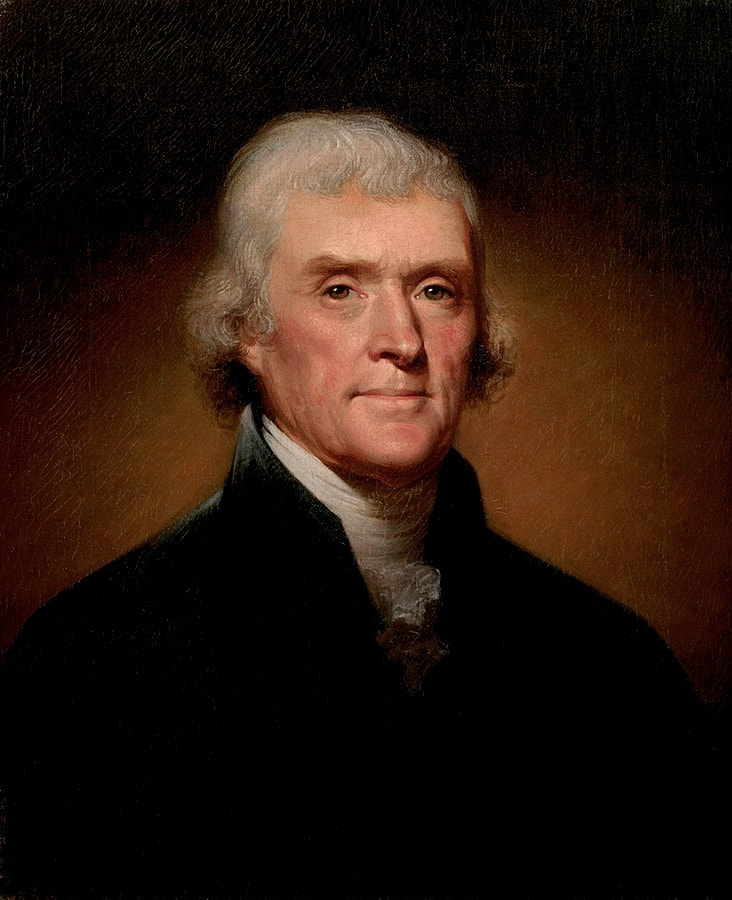

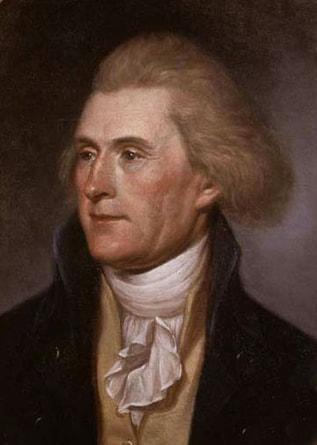

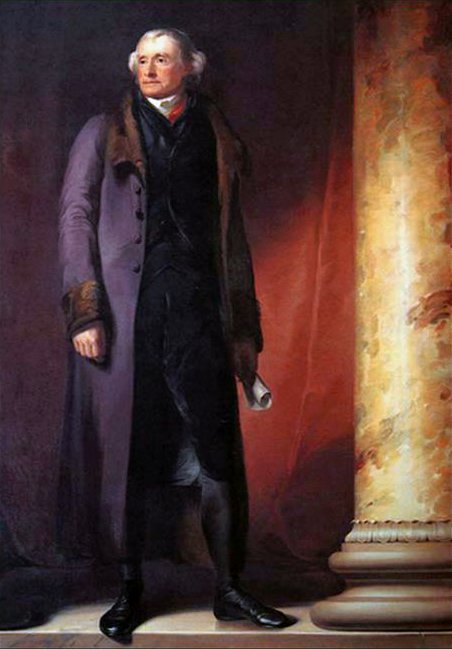

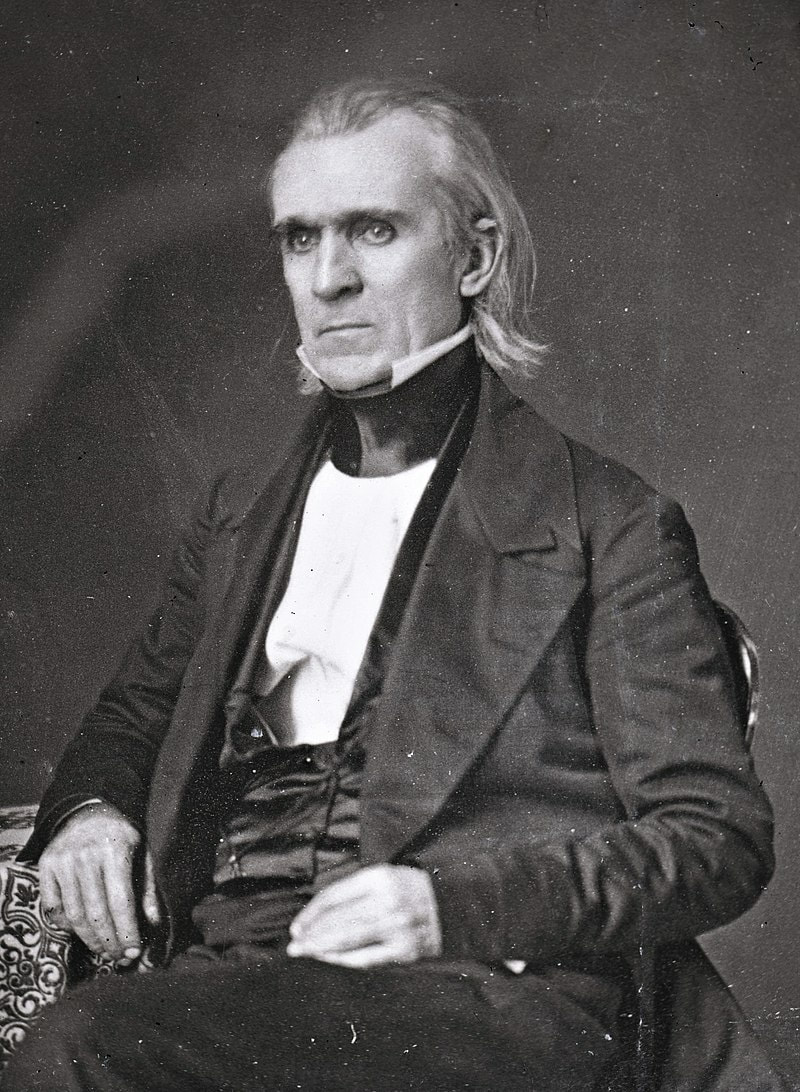

Just outside of Charlottesville, Virginia sits Monticello, the stately home of one of the nation’s preeminent Founding Fathers: Thomas Jefferson. Amidst the unique architecture, mountain top views, and complex history, visitors will also find the final resting place of Jefferson. An obelisk marks the location and is inscribed with an epitaph written by Jefferson himself: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson. Author of the Declaration of Independence of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom & Father of the University of Virginia.” Jefferson believed these three achievements were the greatest accomplishments of his life and hoped that they would serve “as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.” Conspicuous by its absence is one of Jefferson’s most remarkable achievements. One that serves as the high water mark for the few that have obtained it. I’m referring of course to the fact that Thomas Jefferson served eight years as President of the United States. Jefferson thought so little of his time in the White House that he seemed not to care if others forgot all about it as well. The great irony in this of course is that Thomas Jefferson thought rather highly of his election in 1800, referring to it as the “Revolution of 1800.” After 12 years of Federalist control of the government by Washington and Adams, with the help of Alexander Hamilton, the new federal government, with its taxes, promotion of commerce, and harsh dealing with decent, had in Jefferson’s view, betrayed the spirit of 1776. His ascension to the nation’s highest office would be a continuation of the work begun at Lexington and Concord. And yet, in the end he didn’t think too highly of his time as Chief Executive. This inconsistency, while obvious, should come as no surprise to students of Jefferson. His entire life was a contradiction. He detests cities, yet he reveled in the salons of Paris. He attacks the expansion of government power, yet further expands it once in office. And most notable, he penned the immortal words that “all men are created equal” and lamented the evils of slavery, yet in his lifetime he owned over 600 human beings. Volumes have been written about Jefferson’s complex life. His incredible contribution to the founding of the world’s greatest democracy, juxtaposed against his own moral failings and hypocrisies. These are important legacies that warrant study, examination, and debate. However, for the purposes of this blog entry I will do my best to focus on Jefferson’s time in the White House, his Presidency. With that said, Thomas Jefferson’s ascendency to the Presidency began some ten earlier when he became America’s first Secretary of State. Having served as Minister to France during the years of the Confederation, Jefferson was more than qualified to be the nation’s top diplomat. Jefferson was a valued and trusted member of President Washington’s cabinet. However, early on Jefferson began to realize that his vision for America differed greatly from Washington and, more importantly, the President’s right hand man Secretary of State Alexander Hamilton. From their interpretation of the Constitution, to economic and monetary policy, to the use of federal power, and most importantly regarding foreign policy Jefferson and Hamilton stood at opposite ends of the political spectrum. The two men would become the de facto leaders of the nation’s first two political parties: the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Washington, though he claimed no party, was clearly in the Hamilton camp. He was a Federalist. Jefferson thought it best to resign his post in the cabinet and begin laying the groundwork for a presidential run of his own in 1796. When Washington declined to run for reelection in 1796, the Federalists rallied behind Vice President John Adams, the Democratic-Republicans supported Jefferson. In the end, Adams carried the day. However, in accordance with the original wording of the Constitution, as runner-up Jefferson became Vice President. Over the course of the next four years, Jefferson used his largely ceremonial role to undermine everything the President, his former dear friend, John Adams did. While Adams was busy battling his own party to keep the nation from plunging headlong into a potentially disastrous war with France, Jefferson was busy unifying his new party. When Adams foolishly signed into law the authoritarian Alien and Sedition Acts that made it a crime to publicly criticize the President, Jefferson and his trusted lieutenant James Madison rallied the states to oppose the laws. When 1800 came, Jefferson and Adams would once again square off. This time, the beleaguered Adams had little chance of winning. However, this time there was also the problematic addition of a third candidate, another Democratic-Republican, Aaron Burr, complicating the race. In the end, Jefferson and Burr tied in the electoral vote. The nation had its first electoral crisis. With no presidential candidate receiving a majority of the electoral vote, it was up to the House of Representatives to choose the winner. It was at this time that Jefferson’s old nemesis, Alexander Hamilton, provided an unexpected assist. Hamilton wrote to members of the House urging them to support Jefferson. “Mr. Jefferson, though too revolutionary in his notions, is yet a lover of liberty and will be desirous of something like orderly Government – Mr. Burr loves nothing but himself – thinks of nothing but his own aggrandizement – and will be content with nothing short of permanent power.” Jefferson carried the day and was elected the third President of the United States. Burr, became Vice President. Within a few years, plans were set in motion to amend the Constitution and change the method of choosing a Vice President. On March 4, 1801 Thomas Jefferson walked to the unfinished Capitol for his inauguration. He attempted to strike a unifying cord in his address when he proudly proclaimed “We are all Republicans. We are all Federalists.” However, make no mistake about it. Jefferson saw his election as a Revolution and would have little use for Federalists in his administration. He immediately sat about enacting his Republican agenda for America. He pardoned the Democratic-Republican newspaper editors, “martyrs”, that had been prosecuted under the baneful Alien and Sedition Acts. He eliminated all internal taxes, shrank the size of the Navy, and began to pay down the national debt. In addition to these tangible changes, he also felt it important to make symbolic changes that reflected the Republican nature of the Presidency. After all, the President is not a king. He did away with nineteenth century formalities. Hosting casual dinner parties rather than formal banquets. He would often answer the White House door himself, occasionally in his casual evening attire. Jefferson was making his mark on the Presidency. Soon, as would be the case with every man to hold the office, the political goals of the campaign would come face to face with the realities of Presidential leadership. It was Thomas Jefferson, the man who wished to shrink the navy and had little use for an army, that would be the first American President to lead the nation through a successful overseas military conflict. The Barbary Wars were the result of North African pirates seizing American merchant ships and demanding bribes for the release of prisoners. President Jefferson ordered the Navy to the Mediterranean to confront the pirates and blockade Barbary ports. After several years of limited conflict, and an unlikely alliance with Sweden, the conflict was resolved and American sovereignty was respected. In 1803, Jefferson stumbled into the deal of the century. The port of New Orleans, though owned by France, was crucial to American economic interests west of the Appalachian Mountains. Farmers in rapidly growing areas along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers would send their products down the river to New Orleans where it could be stored before being picked up by ocean faring ships that could take it to the ports of the eastern seaboard. Fearing the French, who had only recently acquired the territory from Spain, would shut off New Orleans to American merchants, President Jefferson sent James Monroe and Robert Livingston to Paris with an offer to buy New Orleans and the surrounding area from Napoleon. Much to the surprise of the American envoys, Napoleon made a counter offer. Strapped for cash and seeing little value in maintaining a costly presence in North America, Napoleon offered to sell the entire Louisiana Territory, more than 800,000 square miles, to the United States for the bargain price of $15 million. The Americans took the deal and returned home with news of their purchase. Jefferson, though enthusiastic at the prospects of adding so much territory to the United States, was conscious stricken with the purchase. He had long attacked previous Federalist administrations for overstepping constitutional bounds in their pursuit of their goals. Jefferson claimed to be a strict constructionist, meaning that the President and Congress could only exercise those powers specifically granted to them by the Constitution. There was no room for implied powers. Yet, nowhere in the Constitution is the President granted the authority to purchase territory. If Jefferson supported the Louisiana Purchase, he would be betraying his most fundamental of principles. But what a deal! Jefferson signed the treaty and Congress, filled with Democratic-Republicans accepted the deal. With the stroke of a pen and quick vote in Congress, Thomas Jefferson doubled the size of the United States. Shortly after the purchase was made, Jefferson commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to lead the Corps of Discovery for the purposes of mapping and exploring the new American territory. The Lewis and Clark Expedition would become a great American epic, but more importantly bring back a wealth of scientific and cultural knowledge regarding the people, plants, and animals for western North America. Jefferson’s willingness to betray his principles in making the Louisiana Purchase and eagerness to send the Corps of Discovery reflect his vision for America. Thomas Jefferson, like many of his Democratic-Republican followers, had a unique vision of American liberty. To Jefferson the quintessential American was the yeoman farmer. There was no better expression of American freedom than a small landowner who provided for his family through the fruits of his labor. Though educated and connected to the larger nation civically, he was largely free of what Jefferson viewed as the agents of oppression: a strong federal government, banks, the marketplace, and organized religion. These had been the oppressors during the Revolution and Jefferson had no taste for them in the American experiment. In order for American citizens to live out this view of liberty required, above all else, land to farm. The Louisiana Purchase provided the United States a seemingly endless tract of land to fill with virtuous, freedom-loving, republican farmers. In the pursuit of this noble goal, previous concerns about fidelity to the doctrine of strict constructionism would take a back seat. Of course, Jefferson’s dream for America did not come true. Though he wouldn’t live to see it, the men and women who eventually settled the land he purchased in 1803 would become serfs to banks, world markets, and corporate interests. It was not the agrarian republic he imagined. But in the final analysis, Mr. Jefferson’s purchase has been incredibly beneficial to the United States as a whole. As Jefferson’s first term was nearing an end, he faced a new problem, his Vice President. With the adoption of the Twelfth Amendment altering how Vice Presidents were chosen, Aaron Burr was dropped from the Democratic-Republican ticket. Ever the politician, Burr quickly set his sights on another, no doubt more prestigious office, in the upcoming election. Burr announced his candidacy for Governor of New York in 1804. Federalist leader Alexander Hamilton once again used the power of his pen to publicly denounce Burr as unfit for office. When Burr was defeated, he blamed Hamilton for yet another failed campaign. Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel, which the former Secretary of Treasury accepted. Burr shot and killed Hamilton on July 11, 1804. The Vice President was charged with murder, though the charges were later dropped. One would imagine that sitting Vice President being charged with murder would be the oddest part of the story, and yet the complications go further. After his term ended in early 1805, Burr ventured west into the Louisiana Territory with a small group of armed men. His plans appeared to have been to somehow provoke an armed conflict with Spain which he would then exploit to seize western land that would then break away from the United States. Several years later, when President Jefferson learned of his former Vice President’s odd conspiracy, a warrant was issued for his arrest. This time, the charge was treason. A charge for which he was acquitted due to lack of evidence. With a new running mate, George Clinton of New York, Jefferson was reelected in 1804 in a landslide. His first term had seen the doubling of the United States, a successful military conflict, the reduction of taxes and the national debt, and the addition of a new state, Ohio, to the Union. It was by any measure a successful four years. However, as would be the case with every other president in the years to come, his 2nd term would not go as smoothly as the first. Thomas Jefferson’s second term was consumed with foreign policy. Great Britain and France had been at war for some time and Jefferson had largely managed to keep the United States away from the conflict. Things changed in 1805. Though highly critical of Great Britain (see 1776), Jefferson was smart enough to know that positive economic relations with the British would prove invaluable to the economic prospects of the United States. At the same time, Jefferson loved France. While serving as ambassador to France in the 1780s, he had consulted with revolutionary leaders who were overthrowing the French monarchy. He would urge President Washington to support the French in their war against England in the 1790s. Now as President of a young and fragile country, he was caught between his head and his heart in terms of which nation to support in the war between the two European rivals. Jefferson hoped to remain neutral in the affair and continue trade with both belligerent nations. However, as the war intensified so did the tactics. Both the British and French navies began seizing American merchant vessels bound for their enemies' ports; a clear violation of American sovereignty and neutrality. The British were far more heavy-handed in their dealing with Americans. They seized far more ships and began forcing American sailors into service to the British navy; a practice known as impressment. After initially attempting to cool relations with the British, hostilities intensified as a result of the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair. A British naval vessel attempted to board an American ship. When the Americans refused the British opened fire killing several American sailors. Frustrated with the attack, but unwillingly to be drawn into a war, President Jefferson thought he could use American economic power to lure both France and Great Britain to the negotiating table in order to get them to respect American rights. He was wrong. With the President’s support, Congress passed the Embargo Act of 1807. Essentially, the Act cut off all trade with all foreign nations. In theory, the lack of American goods would prove disastrous for both sides and they’d be eager to reach a peaceful settlement. In reality, neither Britain or France paid much attention to their little brother across the Atlantic. They didn’t need American goods or raw materials. The Embargo did nothing to end the conflict, while at the same time wreaking havoc on the American economy. Trade was the backbone of the American economy, particularly in New York and New England. Rather than punishing London and Paris, Boston and Philadelphia suffered the consequences of Jefferson’s decision. It is rare that the origins of an economic recession can be so easily traced to a single event. However, the genesis of the 1808 recession can be found squarely on Jefferson’s desk. The economy was in shambles as was Jefferson’s second term. As 1808 approached, Jefferson honored the tradition set only 12 years early by George Washington and declined to seek a 3rd term. He was weary. Plagued by headaches and disillusioned with politics, Thomas Jefferson began to loath the presidency and wanted nothing more to do with it.

Jefferson remained active during his retirement. In addition to maintaining correspondence with old colleagues and current political leaders, Jefferson continued his pursuit of creating a virtuous, well-educated citizenry. It was during these years that he accomplished one of the landmark achievements of his life: the founding of the University of Virginia. The Jeffersonian vision for America had education at its core. In founding UVA, the former President ensured thousands of Americans would have a solid foundation in their “pursuit of happiness.” It was also during these final years that Jefferson rekindled a friendship with his former revolutionary brother turned political enemy, John Adams. The two elderly Founding Fathers, having not spoken in years in 12 years, gradually began sending letters to one another. Over the next 14 years, the two corresponded more than 150 times discussing everything from the news of the day to reflecting on their roles in the revolution. The letters serve as a treasure trove of insight into the two greatest minds of the American Revolution. Thomas Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, the 50th Anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. In a stroke of fate, John Adams passed away on the same day a few hours later. Following his passing, arrangements were made in line with Jefferson’s wishes. He was buried at Monticello, the obelisk he designed and the epitaph he penned were displayed at his resting place. Though Jefferson made no mention of his presidency, the nation was unquestionably shaped by it. He doubled the size of the nation. He brought republican principles to the office of the office of Chief Executive. He was a champion of limited government, but was willing to use the power of the government in pursuit of higher principles. He was flawed, a hypocrite, he made mistakes, but he believed in the American experiment. In short, he was an American.

0 Comments

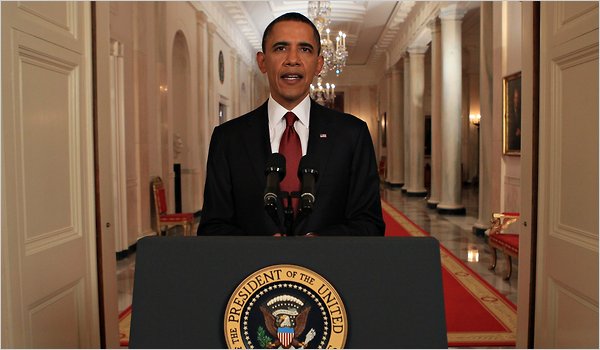

I didn’t want to write this. Perhaps that’s why it has been more than a year since I last updated my presidential rankings blog. I apologize to my three avid readers. The reason is simple. As a history teacher, most folks (including students) respect your opinion when discussing American history even if they don’t agree with it. They assume, I suppose, that you’re well-versed in the subject, have studied it extensively, and have come to your conclusions in a logical and respectable manner. Yet, when you apply the same methods of analysis to modern politics that you used when studying the past, they automatically pass judgement. If they agree with you, you really know your stuff. If they disagree, you’re a political hack whose perspective shouldn’t be taken seriously. This is why I didn’t want to write this blog entry and why I don’t like teaching about 21st Century American political history. That being said, take everything I’ve written with a grain of salt. If you agree, great. If you don’t, it’s a free country and you’re entitled to your opinion. Here goes… 2004 was a big year for a political nerd like me. It was the first election in which I was legally old enough to vote and I was excited. I was turned off by the Bush Administration. The disastrous war in Iraq that started during my senior year of high school was the first event that really caused me to examine my own political beliefs. I had made the decision that I was going to vote for Senator John Kerry. However, as excited as I was to vote. As enthusiastic as I was with the prospect of making George W. Bush a one term president, I can’t say that I was overly enthusiastic to vote for John Kerry. The Massachusetts Senator was more than qualified. He had served our nation during Vietnam and I found that I agreed with him on many policies. But I didn’t feel any political excitement. Truth be told, I didn’t even support Kerry in the primary. I was hoping General Wesley Clark would win the nomination. Nevertheless, Kerry was the nominee and he had my vote. However, as I sat watching the 2004 Democratic National Convention I felt political excitement for the first time. A State Senator from Illinois came to the podium to deliver the keynote address. The speech he delivered that night would change his political life and set into motion a series of events that would forever change America. Like the vast majority of Americans, I had no idea who Barack Obama was in 2004. Within a few years, everyone in the country would know his name and, likely, have a strong opinion about him. “This guy should run for president.” I thought. As it turns out, millions of other Americans had the same idea.

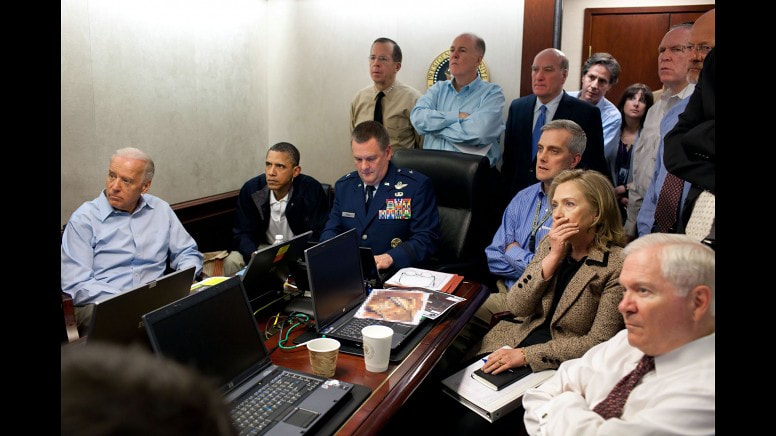

Barack Hussein Obama was elected President of the United States in November 2008. His election was historic by any measure. The biracial son of a Kenyan father and a white mother from Kansas, Obama’s story is one that could seemingly only happen in America. He managed to defeat the Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton during the primary before challenging Senator John McCain in the General Election. It was during the fall campaign that the juggernaut that was the Obama Campaign gained traction. A multiracial coalition of young voters, midwestern moderates, and coastal liberals proved to be too much for the McCain campaign, and many down-ballot Republicans, to overcome. There was a very real sense when Americans went to the polling place in 2008 that they were participating in something historic. After all, Barack Obama is black. Had he been born a little more than 100 years earlier, he would have legally been considered ⅗ of a person and had no legal rights. Now, he was President of the United States. Historic is an understatement. Obama’s election represented a level of racial progress that previous generations could scarce have imagined. America had resoundingly chosen a black man to lead the nation. No one should diminish the significance of such an event. And yet, Obama’s ascent to the nation's highest office exposed the ugly truth that America had not achieved the post-racial society that so many pundits of the time predicted. Racism still exists and, as enterprising politicians soon learned, could be used to rally support for their cause. Obama and his family were attacked because of the church they attended. Ironically, at the same time, the President, a professing Christian, was labeled a secret Muslim hellbent on implementing Sharia law on an unsuspecting nation. He and his wife were depicted in political cartoons as terrorists, black nationalists, and various other hateful caricatures. Right wing media questioned why the Obama’s didn’t have any “white dogs” in the White House. All the while, mainstream conservative commentators proclaimed that the President had a “deep-seated hatred for white people” and played songs such as “Barack the Magic Negro.” This all culminated with the rise of the racist lie that Barack Obama was not born in the United States and therefore was an illegitimate president. This lie was perpetuated by "Celebrity Apprentice" host and one time steak pitchman Donald Trump who used it to launch his political career. Anything that could be used to otherize Barack Obama was used to undermine his presidency. These were not principled policy debates. This was fodder for a quickly shrinking segment of voters who felt threatened by an ever changing America. An America represented by Barack Obama. No other president in American history had to endure attacks of such a vitriolic nature. In spite of this, Obama left office after two convincing elections with an approval rating approaching 60%. No President since Roosevelt had entered the White House with such a challenging economic situation. From the final months of 2008 through the first 3 months of Obama’s presidency in 2009, the nation was averaging more than 700,000 job losses per month! The economy would continue to see negative job numbers until the earliest months of 2010. As it approached the end of his first year in office, the Obama Administration was staring at double digit unemployment and a rapidly contracting GDP. Such dire economic numbers are generally the opening line of political obituaries. Yet for Obama they were merely the first tremulous act in a successful two-term presidency. In the final days of the Bush Administration, during the earliest days of what would come to be known as the Great Recession, the financial sector was on the verge of collapse. The failure of Lehman Brothers, the stock market crash, and a hemorrhaging housing market had many economists worried that we were heading for a 1930s level economic catastrophe. President Bush proposed the hugely controversial Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (aka The Bank Bailout) that begrudgingly received bipartisan support, including by then senators Obama and McCain, which may have prevented a second Great Depression, but did little to address the long term impact of the crisis. Those consequences would have to be addressed by the next administration. So how did President Obama try to fight the recession? In February 2009 Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The price tag of $787 billion seems small in comparison to the spending spree we’ve seen in recent years, but at the time it was hugely controversial. Conservatives attacked it as government overreach and liberals attacked it as too limited. The law included government investment in healthcare and infrastructure but also included targeted tax cuts. The struggling automotive industry was assisted through loans and American consumers benefited from the “Cash for Clunkers” program which increased demand. Meanwhile, the Dodd-Frank Act reformed Wall Street regulations to try to prevent future financial crises and the Credit CARD Act sought to ease the debt burden faced by millions and outlaw predatory lending practices. By late 2009, the economy was showing steady signs of improvement. The job market however, was the last to recover. The Obama Administration was saddled with frustratingly high unemployment through much of its first two years in office. However, once the job market began to rebound near the end of 2010, it began a string of 75 straight months of job growth. By the time he left office in January 2017, unemployment was 4.7% below historic averages. In the post-WWII era, Obama trails only Clinton and Reagan in terms of net job creation with more than 11 million jobs added. On the world stage, Obama had mixed results. From the signing of the Paris Climate Accords to the seemingly intractable American involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. Obama focused heavily on repairing relationships with NATO allies after years of disagreements between the US and Europe during the Bush years. While he no doubt made progress in the area of climate and counter terrorism, he was rightfully criticized for downplaying the threat posed by Russia; going so far as to mock Republican candidate Mitt Romney for voicing concern during a 2012 presidential debate. The Middle East was a focal point of foreign policy during the Bush years, and the Obama Administration would be no different. Early in his presidency, Obama fulfilled a campaign promise by delivering a speech in Cairo, Egypt aimed at addressing the increasingly strained relationship between the United States and the Arab world in the years following 9/11 and the War in Iraq. Middle East policy would be a challenge for Obama just as it had been for many of his predecessors. Obama pursued a policy of direct engagement, not only with our partners in the region, but also with our advisories. This can be seen with his multilateral negotiations with Iran that resulted in the much debated Iran Nuclear Deal. When the Arab Spring erupted resulting in mass protests against authoritarian regimes in the region Obama had to walk a tightrope between being supportive of the protests, while also acknowledging the instability that would inevitably come to the region. Instability that contributed to the disaster in Benghazi, Libya and the increase in violence in Egypt, Iraq, and Syria where ISIS soon began to take hold. Obama’s approach to ISIS was to rely upon international partners, including those in the region, in support of limited military engagement by US forces. A policy, that while slow and frustrating, seems to have been largely successful. However, whatever his failures or successes, Barack Obama’s foreign policy will always be remembered for a renewed focus on al-Qaeda and bringing to justice the mastermind of the September 11th attacks: Osama bin Laden. After an initial international manhunt following 9/11 the hunt of bin Laden had become an afterthought for the Bush administration by 2008. When asked about finding the al-Qaeda leader during the 2008 campaign, then candidate Obama promised to once again make it a priority and suggested that he would be willing to take unprecedented steps to locate bin Laden. Those steps were taken in the Spring of 2011, when the CIA reported that they believed they had located bin Laden in a compound in Pakistan, our ally in the War on Terror. Obama made the controversial decision to send a team of Navy SEALS to the compound to conduct a raid to kill bin Laden and recover his body. The raid was a success, al-Qaeda was weakened, and justice was done. Much like foreign policy in general, Obama’s handling of the so-called War on Terror was a mixed bag of successes, frustrations, and failures. The killing on bin Laden and the weakening of al-Qaeda was no doubt a success. However, the expanded use of drone strikes to target suspected terrorists, and his failure to close the prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba highlight the complicated nature of Obama’s efforts. However, in the years since leaving office it appears the Obama Administration, like the Bush Administration before it, maintained a vigilant and steady approach to addressing the national security of the United States no doubt making the US less vulnerable to foreign attack than two decades earlier. Barack Obama impacted the judiciary in a significant but limited way. During his first term, Obama appointed two new justices to the Supreme Court Sonia Sotomayer, the first Latina member of the court, and former solicitor general Elena Kagan. However, beyond these two appointments, Obama’s ability to appoint justices in accordance with his constitutional duties would be scuttled by the man who would prove to be his arch-nemesis: Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky. In 2010, McConnell stated that making Obama a one-term president was his most important goal. Of course, McConnell failed miserably in this pursuit as Obama was reelected by a strong margin in 2012, however in terms of hurting the Obama agenda, McConnell used every tool in the tool box. The filibuster is a senate rule adopted in the early 1800s, but rarely used until the latter half of the twentieth century, that requires a 60 vote margin in order to pass most legislation in the US Senate. You will not find this rule in the Constitution. For decades the Senate passed a tremendous amount of legislation passed without the threat of a filibuster, and when one was used it required that a senator (or group of senators) take the floor and refuse to yield. As time went on, the filibuster morphed into what it is today, a procedural vote that requires 60 senators to agree before any issue can advance. Mitch McConnell used this to his benefit, at times bringing the Senate to a halt. McConnell, the Senate minority leader, instructed his caucus to stop everything; most importantly judicial appointments. The GOP minority filibustered more judicial appointments in Obama’s first 5 years than the previous 40 years combined. Vacancies on district and appellate courts were left unfilled for months, sometimes years, at a time. It is for this reason that Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid invoked the hyperbolically named “nuclear option” and removed the filibuster for all presidential appointments except for Supreme Court nominees. When McConnell became the Majority Leader in 2015, he doubled down on his obstruction using his new power to prevent even more appointments going so far as to refusing to even hold a confirmation hearing for Obama Supreme Court Nominee Merrick Garland to fill the vacancy created by Justice Antonin Scalia’s death. In doing so, McConnell personally changed the size of the Supreme Court to 8 justices for an entire year. In two years under McConnell’s leadership, the Senate confirmed fewer justices (20) than any other Congress had in more than 50 years. By the time he left office, there were 105 vacancies on the federal bench. Obama nominated judges to fill many of these vacancies while Mitch McConnell refused to allow the Senate to vote on their confirmation. Congressional obstruction and gridlock came to define the Obama years. A new GOP emerged in the post-Bush years. No longer united by conservative values, they were now singularly defined by the opposition to Barack Obama. Not since the earliest days of the Whig Party in the 1830s had a political party been united by nothing more than opposition to a single president. Issues that used to be table stakes for Congress like raising the debt ceiling and confirming secondary level executive branch appointments, had now become political wars of attrition. For the GOP, opposition to Obama was the coin of the realm. Even when the bipartisan “Gang of Eight” put forward an Immigration Bill that easily passed the Senate, the Republican Speaker of the House John Boehnor (who supported the bill) refused to bring it to a vote. It would have passed with bipartisan support, but the extreme right of his party opposed it because it would be signed into law by President Obama. Many of the folks that were swept in office in 2010 and beyond came to Washington with little interest in governing. They came to disrupt, obstruct, and grandstand. A critique shared by their former leader, Speaker John Boehnor: "Most of these guys who poke their heads up and vote 'no' on every compromise claim they're doing it all for 'conservative principles' don't actually give a sh-- about fiscal responsibility. It's not really about the money. It's not about principle. It's about chaos." No doubt, many in the TEA Party movement were genuinely concerned about taxes and the growth of government, but many others had little interest in promoting a governing agenda for America. Their opposition was not based upon deeply held ideological convictions. Their opposition was to Barack Obama the man. A black man that many in their caucus falsely believed was born in Kenya. Fed a daily diet of misinformation from a growing right wing media apparatus that gave a platform to the most extreme views, GOP voters in 2010 and 2014 supported primary candidates that challenged traditional conservative members of Congress that were interested in governing. Over the course of several election cycles, fiscal and culturally conservative Republicans were weeded out in order to make room for performative propagators of outrage and conspiracy. A sad reality that has persisted in the years following Obama’s departure from Washington. The inability of Congress to govern through much of Obama's presidency will always be a dark spot on the history of House and Senate; making a mockery of the Founders' intentions for the First Branch. It was a result of this legislative dysfunction that Obama leaned into executive power. To his critics, Obama's use of executive orders was proof that he was a tyrant. Meanwhile, his liberal allies often lamented that he didn't exercise more executive authority. For the record, Obama issued fewer executive orders than either of his previous two predecessors and in eight years in office issued only 56 more than his successor did in four years. Such executive action can only be properly understood when presented within the context of legislative inaction. After the horrific mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012, President Obama issued 23 wide-ranging, but limited, executive orders aimed at reducing gun violence and enhancing school safety while calling on Congress to do more. In typical Senate fashion, a minority of Senators used the procedure 60 vote threshold to block passage of two bipartisan bills designed to keep deadly weapons out of the hands of individuals determined to hurt other people. Obama's executive orders would be the only federal response to the tragedy. However, some orders were more impactful. When Congress failed to pass the aforementioned bipartisan immigration reform bill. Obama issued a number of executive orders to address the broken immigration system. None more meaningful or beneficial than the Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals, better known as DACA. The action protected undocumented immigrants who were brought. to the United States as children, from deportation. While it did not provide a pathway for citizenship, it created more opportunities for the Dreamers to work, get an education, and continue to build a life in the only country most had ever known. For all the discussion of executive orders, no president can be considered successful unless they have at least one significant legislative achievement during their time in office. For Barack Obama, that achievement was the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, better known as the ACA or “Obamacare.” Since the days of Theodore Roosevelt, Presidents and Congress have debated the best way to provide healthcare to the American people. Some have argued for a single-payer system with government control like those in much of Europe. While others have argued for free market solutions without the needless bureaucracy of government. In the end, the healthcare system created by the United States was one largely run by the private sector. Following WWII, health insurance became a staple of benefit packages offered by employers. The concept of tying one's healthcare to one's employer is as American as apple pie. As the decades passed the healthcare system was gradually regulated and the government began to play a greater but still limited role. Most of this change occurred during President’s Johnson’s “Great Society” reforms. And yet, despite the popularity of programs like Medicare and Medicaid, Americans have always been leery of government regulation of healthcare. Decades of insurance company lobbying and Cold War era fears of socialism made tackling America’s healthcare crisis a political third rail. See early 90’s Hillary Clinton. However, by the turn of the century American were more unhappy with their healthcare coverage than ever before. On average American’s paid more for healthcare than comparable nations and received far worse outcomes. The United States had the best doctors and hospitals in the world and yet they were financially off limits to the majority of Americans. Americans could be denied healthcare due to a preexisting condition, meet lifetime maximums in terms of coverage, and young adults could be kicked off their parents' coverage. The Great Recession exasperated the problem. With healthcare coverage tied to employment, millions of Americans lost their healthcare coverage when they were laid off through no fault of their own. The challenge of reforming healthcare had crippled the most talented of politicians in the decades leading up to Barack Obama’s election. And yet, where others had failed, Obama succeeded.

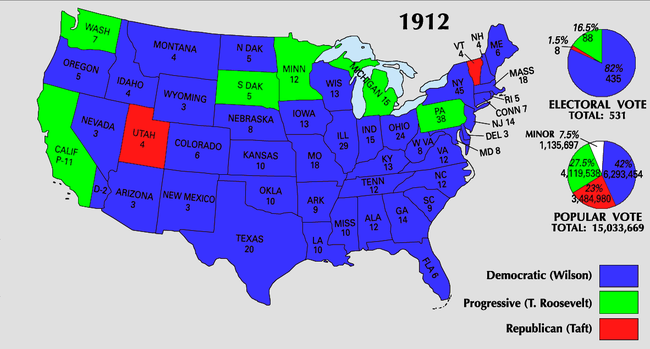

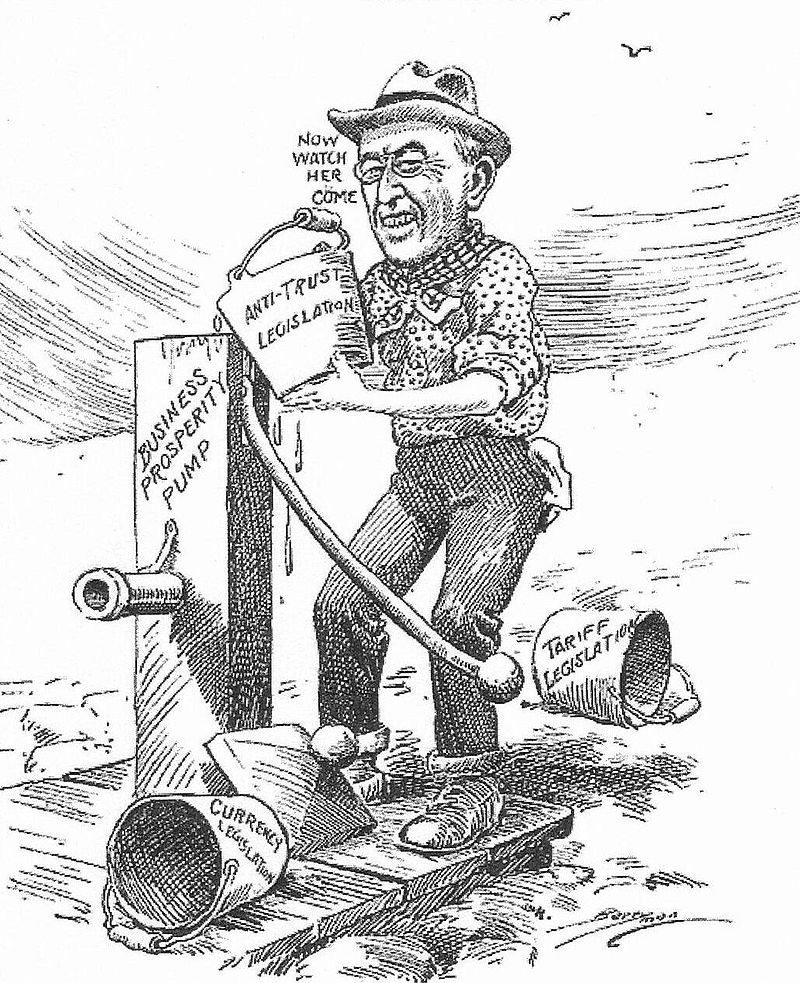

The legislative healthcare battle that occurred during Obama’s first term demonstrated the President’s pragmatic progressivism. He wanted broad support for the bill not only from progressive Democrats, but from moderates, and willing Republicans as well. In order to achieve this, some ideas were off the table. Far left ideas such as a single-payer system and eventually even the more moderate public option were not included in the final bill. Instead, Obama opted for a free market approach that would keep insurance companies in place and allow them to remain profitable, meanwhile the government would set new standards while also supporting families (and states) for whom healthcare coverage was too burdensome. “Obamacare” was modeled after a plan put in place by the Republican Governor of Massachusetts and 2012 presidential rival Mitt Romney. Obama went so far as to conduct negotiations with congressional GOP leadership on live television. However, in the end not one Republican member of Congress would vote for the final bill. Despite huge majorities in both the House and the Senate, Democratic leadership was forced to use a budget reconciliation strategy to pass the bill, which was signed into law by President Obama on March 23, 2010. Pundits predicted that the controversial new law would spell the end of Obama’s presidency and those of his Congressional allies. No doubt, for many Democratic members of Congress from moderate and conservative leaning districts, it did mean the end of their time in office in November of 2010. But for Obama, it meant a convincing reelection. Despite the disastrous rollout of healthcare.gov, the ACA has endured and has gained in popularity with each passing year. Lifetime maximums and denial due to preexisting conditions are things of the past. Three times the law has been challenged before the Supreme Court and three times it has been upheld. When the Trump administration made repealing Obamacare a signature part of their agenda in 2017, many assumed the law would be destroyed because of the Republican majority in the House and Senate. And yet, in a twist of fate, it was Republican Senator John McCain, Obama’s 2008 opponent, together with Republican Senators Collins and Murkouski that ensured that the law would survive. Before passage of the Affordable Care Act, more than 60 million Americans lack health insurance. In 2021, more than 90% of Americans have healthcare coverage in some form and premiums rose at a slower rate than before passage of the ACA. Barack Obama, knowing the political minefield he was walking into, famously claimed that he was willing to risk his presidency to achieve healthcare reform. Now, 11 years later it is arguably the most lasting part of his legacy. After 8 years of a politically fraught presidency, Barack Obama left the White House. He had presided over nearly 6 straight years of economic growth, a sizable reduction in the number of Americans lacking health insurance, a restoration of American leadership in the world, and a rapidly changing society continuing to grapple with what it means to be an American. In the final analysis, history will remember Barack Obama was a groundbreaking, consequential, effective and successful leader. Ranking presidents is a difficult task. Our country venerates some and demonizes others. With the passing of time, the legacies of some improve as they are reexamined through modern eyes. Conversely, the reputations of others are tarnished as we take a closer look at the opinions they held and policies they pursued which are not in line with modern values. Ranking presidents is hard because they are human beings. Capable of doing good in the world, but also filled with hypocrisies, inconsistencies, and shortcomings all shaped by the time in which they lived. And yet, the student of history must look at the totality of a president's time in office. They must take a full measure of the good and the bad, in order to fairly assess their leadership. Woodrow Wilson presents an interesting challenge. A man whose accomplishments rank among the most noteworthy in American history, but whose personal prejudices will forever mar his presidency. I hope this will be a fair and honest assessment. Woodrow Wilson was an academic. He was born in Virginia in 1856, the son of Joseph Ruggles Wilson, a Presbyterian pastor and professor of theology. Wilson’s family were slaveholders and strong supporters of the Confederacy. As a young boy, he briefly encountered General Robert E. Lee. His southern upbringing would make a lasting impact on him. Not only did it help develop his admiration for the Confederate General, but it also shaped his problematic views regarding race. However, when given the chance, Wilson got out of the South. In 1874, he enrolled at Princeton University to study political science. After graduating he briefly practiced law before enrolling at John Hopkins University to pursue a doctorate, which he earned in 1886. To date, he is the only American President to have a PhD. He began a career as a professor because he enjoyed the prospect of a quiet life of writing and study with the promise of a steady paycheck. And write he did. Throughout his career, Dr. Wilson authored numerous papers critiquing various forms of western democracies, contributed regularly to some of the most respected political science journals of the day, wrote a biography of George Washington, and authored a prominent American history textbook. More about that later. In 1902, Wilson was appointed President of Princeton University. In this role, Wilson was given the opportunity to allow his untapped leadership skills flourish. He gained a reputation as not only an effective and capable administrator, but also a reformer who challenged the status quo. He was an out-of-the-box thinker who had no trouble fundraising for the university. This caught the eye of the New Jersey Democratic Party. Republicans dominated New Jersey politics and the Democrats were willing to take a gamble on an unconventional candidate that offered voters something new. Wilson proved to be the man for the job. Throughout the 1910 campaign, Dr. Wilson proved that his years of studying politics had paid dividends. He burst on the scene as a skilled orator, an independent voice, and a full throated progressive. He railed against the corporate trusts that, for far too long, had maintained a stranglehold on both political parties. He relied upon the support of the powerful Democratic Party bosses, but promised the voters that he would be his own man; independent of the establishment. During a time of progressive change throughout the United States, when prominent leaders of both parties were speaking out on behalf of workers, conservation, and consumer protection, Woodrow Wilson quickly became a leading voice within the movement. Wilson was elected by a sizable margin, bringing an end to an era of Republican dominance in the Garden State. Once in office, he worked with the state legislature to win passage of bills that broke up monopolies, curbed corporate power, and improved working conditions. His success at the state level gained him national notoriety catching the eye of the National Democratic Party. By 1912, Democrats were desperate for a victory. It had been 20 years since a Democrat had been elected President. That man, Grover Cleveland, was the only Democrat that had been elected President in the 47 years since the end of the Civil War. The electoral map simply did not work in favor of the Democrats. If the Democrats hoped to win in 1912, they would need to rally behind a candidate that could energize their traditional base, win over progressive Republicans that were disappointed by President WIlliam Howard Taft, and hope for a miracle. The Democrats found their fresh candidate in Woodrow Wilson. They found their miracle in former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt, who left the presidency in 1909, had become frustrated in retirement. He was frustrated with the lack of excitement in his life. He was frustrated with the direction of the country. Most of all, he was frustrated with his former best friend, President WIlliam Howard Taft who he had hand picked as his successor. Many of the progressive policies that Roosevelt had instituted while president were being rolled back under Taft. President Taft had removed several Roosevelt appointees from prominent positions within the administration. Taft, who had a strict legal mind, also broke up numerous monopolies that were in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Many of these monopolies had been deemed “good trusts” by Roosevelt and he had allowed them to remain in operation during his administration. Teddy took this as a personal offense and vowed to replace Taft as the Republican nominee in 1912. In doing so, he hoped to reignite the progressive wing of the Republican Party. A party that was slowly drifting toward more conservative positions. Twelve states held Republican primaries for the first time in history. Roosevelt won 9 of the 12 contests. However, the vast majority of states held no such primary to send delegates to the convention, opting instead to allow the state party to choose delegates without the input of voters. At the 1912 Republican National Convention, which was dominated by establishment Republican delegates, the conservatives won. Taft was renominated. Roosevelt’s loyalists were livid. They left the convention and established a new political party which they named the Progressive Party and quickly nominated Theodore Roosevelt as their standard bearer. The Republican Party was hopelessly divided. Half stood with the conservative leaning incumbent, President William Howard Taft. The other half rallied around former President Theodore Roosevelt and his far-reaching progressive agenda known as the “New Nationalism”. The divide in the GOP, opened the door for WIlson. In November 1912, despite winning less than 42% of the popular vote, Governor Wilson won a plurality in enough states to win the Electoral College decisively, thus becoming the first Democrat in two decades to reach the nation’s highest office. Not only did Roosevelt’s actions allow for the Democrat Wilson to win election, the progressive voices he took with him from the Republican party would never return to the GOP. Upon entering office in the Spring of 1913, President Wilson set to work winning passage of a number of bills that would make up his “New Freedom” agenda. In order to do this, Wilson believed that the government must act to tear down the “triple wall of privilege” - the tariff, the banks, and the trusts. Wilson believed that these three obstacles were used by the wealthy industrialists to cripple competition, oppress small farmers, weaken small business and labor, all while consolidating their economic and political dominance over America. Within months, Wilson won passage of the Underwood-Simmons Act which reduced the federal tariff that was hurting small farmers at the expense of powerful industrialists. Tariffs provided a large portion of revenue that funded the federal government. Reducing the tariff was sure to cause a hole in the federal budget. Fortunately for Wilson, weeks before taking office the Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which allowed Congress to institute an income tax. As a result, Wilson was able to work with Congress to shift the tax burden off of the working class (the tariff) and toward the wealthy captains of industry via the income tax. Next, Wilson set out to reform the banking system. The American monetary and banking system had been a mess since Andrew Jackson killed the Bank of the United States in the 1830s. Credit was inaccessible to many small farmers and businesses. This coupled with the instability of the American dollar led to numerous economic panics over the past 70 years. Unlike many Western nations at the time, America lacked a national bank. It lacked a single entity to issue currency, safeguard government deposits, set interest rates, and otherwise bring stability to the financial markets. Seeking the middle ground between public and private control of the nation’s financial system, Wilson oversaw the creation of the Federal Reserve System. The new national banking system was largely independent of the federal government. Although the board of governors are appointed by the President of the United States, they serve 14 year terms guaranteeing that no individual administration or congressional majority can exert undue pressure over their decision making. The twelve regional banks oversee the creation of privately owned banks, which in turn hold stock in the federal reserve banks and help to elect the board of directors for those regional banks. Although the nation has still experienced recessions and depressions in the years since it’s creation, the Federal Reserve has done a good job of maintaining the stability of the American dollar and helping to alleviate the worst effects of any economic downturn.

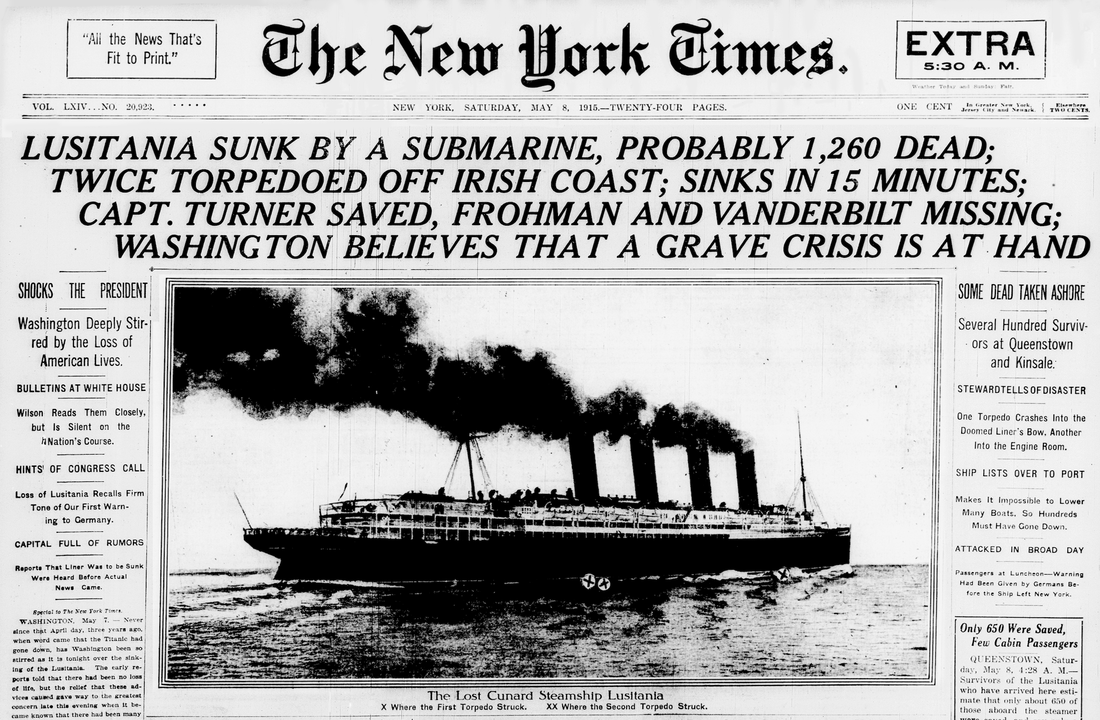

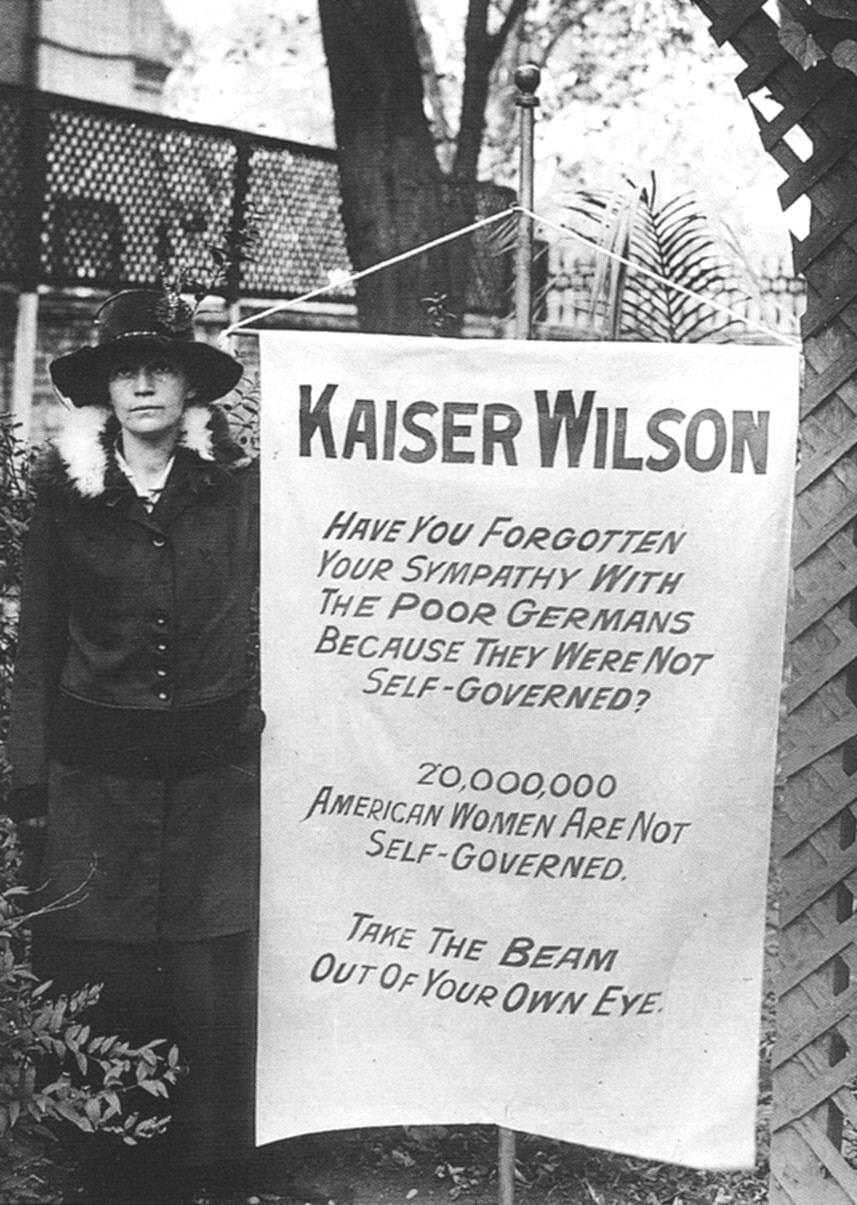

By 1914, President Wilson had proven himself to be one of the most effective administrators in American history. His record of legislative achievement rivals any president before or since his time in office. In one term, he had firmly cemented himself as one of the true champions of the Progressive Era. However, every person has their flaws, inconsistencies, and hypocrites. Woodrow Wilson is no different. While he may very well have been a progressive president, there was one area in which Wilson was not only not progressive, he was in fact rolling back the clock on progress. That area was race. Woodrow Wilson, was a racist. The federal government, having been led by Northern Republican presidents since the days of Reconstruction, was one of the more integrated parts of American society in the early 1900s. Woodrow Wilson, however, believed in segregation and his administration oversaw the implementation of a plan to expand segregation within the civil service. The President’s feeling was that separate work facilities would prevent “friction” between the races. Furthermore, black civil servants were routinely fired and replaced with whites. Such racism shouldn’t be surprising upon further examination. Wilson was a southerner by birth. He admired the South and identified closely with the “Lost Cause” mythology that attempted to rewrite history and portray the Confederates, not as treasonist defenders of slavery, but rather as defenders of states’ rights and their native soil. This was the late-nineteenth, early-twentieth century movement that led to hundreds of confederate statues and monuments being erected throughout the country. As for rewriting history, Wilson, himself the author of an American history textbook, painted a flattering picture of Confederacy, downplayed the horrific actions of the KKK, and portrayed black Americans as an inferior race. Some of his quotes were even used in the infamous film “Birth of Nation” which glorified the KKK as defenders of the South. A film that was screened at the White House. For all Wilson did to create a more fair and equitable society for white Americans, he did the opposite for black Americans. While his views certainly were backward compared to previous progressive presidents such as Taft and Roosevelt, the sad truth is that (according to Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper) Wilson’s views on race probably were far more in line with the average northern white American than we like to admit. In the summer of 1914, the guns of war rang out across Europe. The Great War, as it was known at the time, consumed the western world. American newspapers reported on the carnage daily and American readers were horrified by the reports of trench warfare, deadly new weapons like machine guns and poison gas, and the suffering of millions. While many Americans, a great many of whom were recent immigrants from Europe, sympathized with those suffering across the Atlantic, one thing was abundantly clear: Americans wanted nothing to do with Europe’s war. Wilson was dedicated to neutrality. He had no desire to be drawn into the conflict and would spend the better part of three years taking steps to ensure that American boys were not sent to die on European battlefields. It was this sentiment that propelled Wilson to reelection in 1916 running on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War”. Spoiler Alert: Less than one month after his second inauguration, he asked Congress for a declaration of war. So why did America go to war against the Central Powers in 1917. The answer is a complicated one. From the beginning of the war a American public opinion sympathized with the British and to a lesser extent their allies France and Russia. Americans shared a common form of government, language, culture, religion, and history with Great Britain. It also is worth noting that the United States had far closer economic ties to Britain and France than it did Germany and American banks had made large loans to the British. This is not to say that there weren’t strong feelings on the other side as well. Millions of Americans were of German descent and still had family living in the country at the time of the war. Many German Americans urged caution and neutrality. Meanwhile, Irish Americans were dismayed at the idea that America might in any way lend a hand to Great Britain. However, British propaganda was an effective tool in the United States, often portraying the Germans as butchers. Real world events seemed to support this narrative as well. In 1915, a German U-boat sank the British passenger ship RMS Lusitania killing more than 1,000 passengers including more than 100 Americans. Anti-German sentiment began to rise. In 1917 as the situation in Europe deteriorated, Germany began a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, sinking any and all vessels headed for Britain, passenger and military ships alike. Soon thereafter, the discovery of the Zimmerman telegram further changed public opinion. A coded message from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmerman to the German ambassador in Mexico was intercepted by the British. The Germans, worried that unrestricted submarine warfare might bring America into the war, planned to encourage Mexico to attack the United States in order to prevent the Americans from joining the side of the Allies. In exchange the Germans promised to help the Mexicans recover the territory they had lost to the United States following the Mexican American War in 1848. Americans were angered by the communica and were even more outraged when German U-boats sunk several American merchant ships. Meanwhile, Britain and France braced for a more concentrated attack from the Central Powers. Their unlikely ally Russia was on the verge of defeat and soon would be out of the war. Germany could then focus all of its attention on the western front. On April 2, 1917, Wilson went to Congress and asked for a declaration of war against Germany. In his most famous speech, the idealistic Wilson presented the United States as a peace loving nation that had no choice but to become the defender of democracy throughout the world. “The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make.” Congress obliged and declared war on the German Empire four days later. Despite the soaring rhetoric, support for the war was far from universal. Six Senators and 50 members of the House of Representatives voted against the declaration including Congresswoman Janette Rankin of Montana. Among other reasons, Rankin saw the hypocrisy in supporting a war to defend democracy when millions of women throughout America were still denied the right to vote. Rankin was fortunate enough to live in Montana, a state that did extend the franchise. But most women did not enjoy the same freedom. A few years later, spurred on by protests during the war, President Wilson would slowly lend his support for universal suffrage for women. In 1920, the dreams of generations of suffragettes came true when the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified. As for the war, Wilson now had to sell it to a leery American public. The War Industries Board was created to oversee the creation of a wartime economy. Future president Herbert Hoover was selected to run The Food Administration. American output increased and America was able to feed itself, its soldiers, and its allies during the war. Hoover’s work proved invaluable. As Napoleon once claimed “an army marches on its stomach.” The Allies stomachs were full, while the enemy starved.

Despite the patriotic fervor and growing public support for the war, the Wilson administration turned a blind eye to the injustices happening within the country during the First World War. German Americans were the target of discrimination and harassment. Some German immigrants were tarred and feathered, others beaten, some lost their jobs. Orchestras stopped playing German composers and sauerkraut was dubbed “liberty cabbage.” As black Americans left the Jim Crow south in search of better jobs in the booming industrial north, beginning the so-called “Great Migration”, the northern cities were far from the land of milk and honey many imagined. While there was no Jim Crow in the north, racism and resentment persisted. Violent race riots broke out in the cities of St. Louis, Detroit, and most notably Chicago. The Wilson Administration did little to quell the unrest. While little may have been done to stop the civil unrest, the Wilson Administration had no qualms about stiefly civil liberties. The Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918 gave the federal government the authority to prosecute those who spoke out against the war. Socialists, anti-war “radicals”, and others were arrested and imprisoned. The Supreme Court even upheld the laws as constitutional in the case Schenck v. United States when it claimed that some limitations of first amendment freedoms were permissible. As for the war, America needed an army. It is important for students of history to understand that the United States has not alway been a world superpower with a large powerful standing army. Those are products of World War II and the Cold War. In 1917, the army and navy were small and inexperienced. Congress institution a draft and within months four million men had enlisted. Additionally, women were allowed to join the navy and marines in non combat roles for the first time in American history. African Americans served in large numbers in the army, but did so in segregated units. The new recruits were given a few months of training and shipped “Over There” to join the fight. The American Expeditionary Force under the leadership of General John J. Pershing arrived in Europe without a moment to spare. While inexperienced, the American army offered something that gave the Allies the upperhand: an endless supply of new troops. After years of war, Germany could not continue against the British, French, and their new unscathed ally from across the Atlantic. On the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month of 1918, the Germans laid down the arms. An armistice was signed and World War I came to an end. It was now time for peace. And from the perspective of the victorious British and French, vengeance.

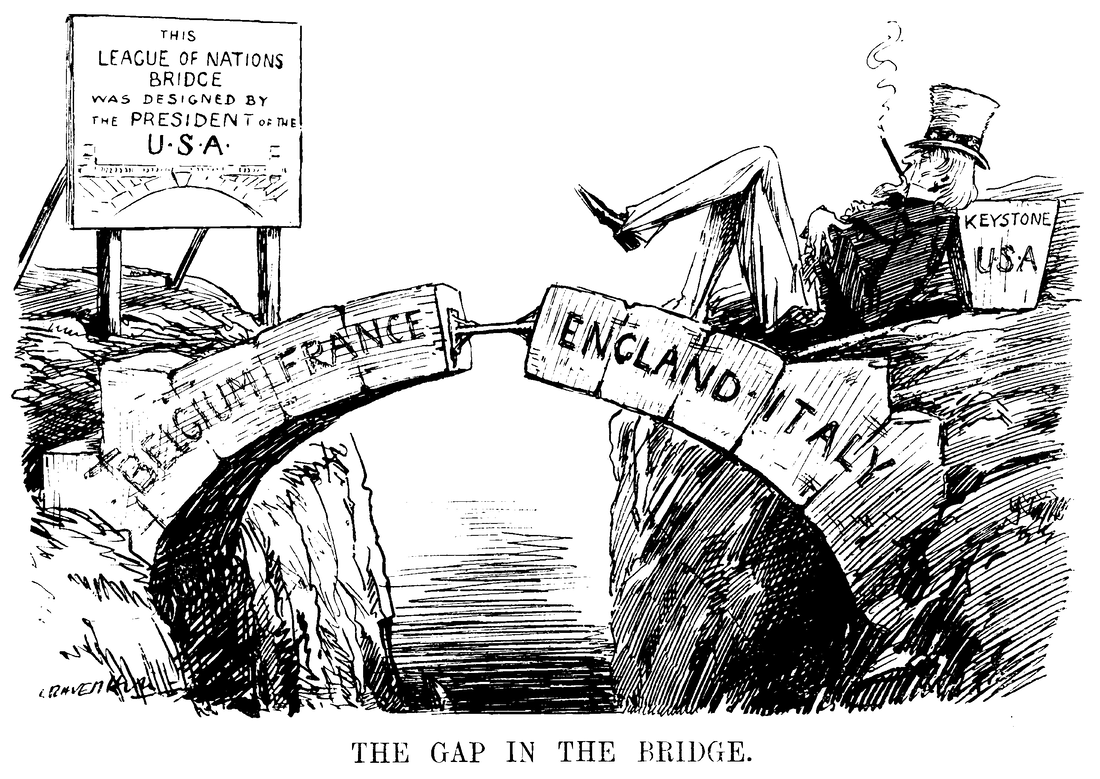

The imperialist Britain and France wasted little time divvying up the territorial spoils of war, taking colonies for themselves from the defeated German, Austrian, and Ottoman Empires. At every turn Wilson butted heads with the allied leaders over their desire for more territory. At the end of the conference Wilson was able to wrangle few concessions from the victors. Most of his Fourteen Points were ignored. However, the League of Nations, Wilson’s brainchild, was included in the treaty. In spite of all of the other shortcomings of the ill-fated Treaty of Versailles, the creation of the League of Nations would be enough to justify the American President’s support. As for the conquered Germans, they were forced to accept the treaty with no input. The Germans had to accept full responsibility for the war and pay reparations. The treaty destroyed the German economy, humiliated it’s people, and would serve as fuel for the rise of Adolt Hilter little more than a decade later. Wilson however, came home with his head held high. The treaty had been signed and the League of Nations was going to be created. A new world order would be established based upon international law and cooperation. Or so he thought. In order for the treaty to be recognized by the United States, it required ratification by the Senate. A Senate that was controlled by the Republicans. The Republican leaders, who were already no fans of the Democratic President, were particularly offended that Wilson had not taken a single Republican member of Congress with him on his trip to Europe. They had been shut out of the negotiations. Now that the treaty was in their chamber, they were going to have their say. The powerful Republican leader Henry Cabot Lodge led the opposition. He made sure that the “world’s most deliberative body” would be deliberative indeed. He held hearings, offered amendments, insisted on more and more debate. The goal was to waterdown the treaty so it would be more favorable to the GOP who were growing more and more isolationist. The President was in no mood for negotiation. Wilson’s hard won prize, the League of Nations, was the greatest point of contention. Many Americans, and certainly the Republican Party, did not want to commit the United States to an organization that might once again draw the country into another European war. Unwilling to compromise with the Senate opposition, the President embarked on a whistlestop tour throughout the country in hopes of winning public support for the treaty. In September of 1919, after giving an impassioned speech in Pueblo, CO Wilson collapsed. After more than a year of leading a war effort, months of negotiations in Europe, and a bitter political fight in Washington, the President’s body could take no more. Days later he suffered a debilitating stroke. With half of his body paralyzed and partially blind, Woodrow Wilson’s presidency was effectively over. For months Wilson was hidden away in the White House. His health was failing him, he saw no one, and he did little to lead the country. The debate over the treaty went on in the Senate. Various versions of the treaty with amendments were offered but no version satisfied enough Senators or the President. The treaty failed. When Wilson learned of the treaty's defeat he remarked “They have shamed us in the eyes of the world.” Having not ratified the treaty, the United States did not join the League of Nations. Without the presence of the United States, whose economy, infrastructure, and population had not been devastated by the war, the League of Nations lacked leadership. It would go on to be impotent organization wholly unable to deal with the gathering storms of the 1920s and 30s. Woodrow Wilson left office in March 1921. For the last year of his presidency, Wilson, having never fully recovered from his stroke, was physically unable to lead. With no constitutional provision to remove him, the country operated with little more than a figurehead throughout 1920. However, within the White House there was, in a way, a new person in charge. Wilson’s wife Edith, whom he had married during his first term, became a kind of presidential gatekeeper. She decided who got to see the president, she reported his wishes to members of the administration, and she determined what information the president would receive on a daily basis. She was, for lack of a better term, a sort of acting president. It was an extraordinary moment at the end of an extraordinary presidential term.

In 1920, America was in a conservative mood. Tired of international involvement, tired of progressive change, Americans voted for Republican Warren G. Harding who pledged a “return to normalcy.” The Wilsonian vision of an activist government and international cooperation was over. Wilson and Edith remained in Washington for the remainder of his life. He marked the 5 year anniversary of the end of World War I by delivering a radio address still holding out hope that one day the United States would once again engage with the world and join the League of Nations. It was not to be. Two months later, Wilson was dead. His body was laid to rest in the Washington National Cathedral. Woodrow Wilson’s legacy is a complicated one. His record of legislative achievement is impressive by any president’s standards. His administration expanded protections for workers, leveled the economic playing field, and stabilized the nations currency. He, however reluctantly, lent his voice to the cause of women’s suffrage and so the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. He successfully led the United States through the First World War. In doing so, he not only helped bring an end to the greatest crisis the western world had ever known, but he also elevated the United States to a position of international leadership. Though the Treaty of Versailles proved to be a disaster for Europe, had the United States ratified it and joined the League of Nations, perhaps the history of the twentieth century would have looked far different. And yet, in sprite of these many domestic and international achievements, Wilson’s shameful record on race will forever cloud his legacy.

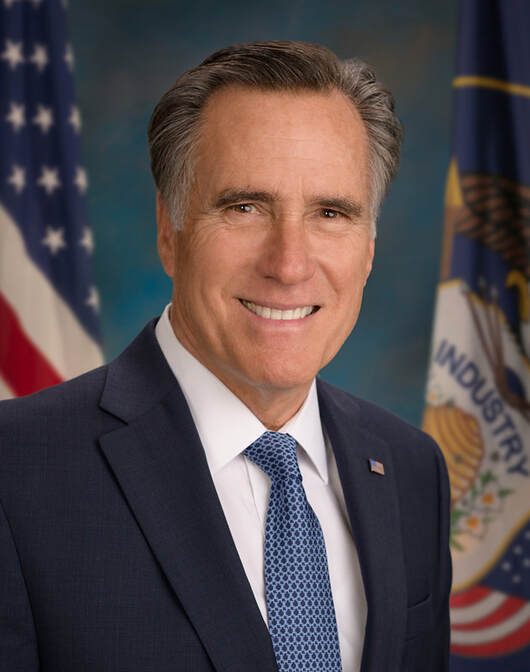

On Wednesday February 5, 2020, Senator Mitt Romney of Utah etched his name into future history books. By voting to convict President Donald Trump of the “high crime” of Abuse of Power, Romney became the only United States Senator in the history of the republic to vote to remove a president of his own party from office. As a result, he will endure the full wrath of Trump, his propaganda apparatus at Fox News, and millions of Trump’s followers. Some have said that Romney’s political career is over. Perhaps, it is. But if it is coming to an end, it would be a shame to allow this moment in history to pass without doing the most possible good for the country while he is still in a position to have an impact . By casting a vote of “guilty”, Mitt Romney demonstrated a quality seemingly absent from Washington: leadership. In 2012, Mitt Romney sought to lead the country and came up a bit short. Much has changed in eight years and in 2020, it is time once again for Mitt Romney to answer the call to lead the country. It’s time for Mitt Romney to run for President of the United States.

First, we must state the obvious, Mitt Romney can not run as a Republican. Donald Trump is the leader of the Republican Party and he will be the nominee in 2020. For Romney to challenge Trump in the primary would be a fool's errand and a waste of resources. For Romney to seek the Libertarian nomination would be disingenuous; he’s not a Libertarian. No, Mitt Romney must run as an Independent conservative candidate. Romney believes in low taxes, deregulation, free trade, and small government. In regards to social issues, he is pro-life and pro-gun, with a sincere religious faith. In short, he is what the Republican Party used to be and many conservatives still are. If a non-MAGA version of conservatism still exists in this country, as I believe it does, Romney’s best bet is to run as an Independent conservative alternative to Trump.

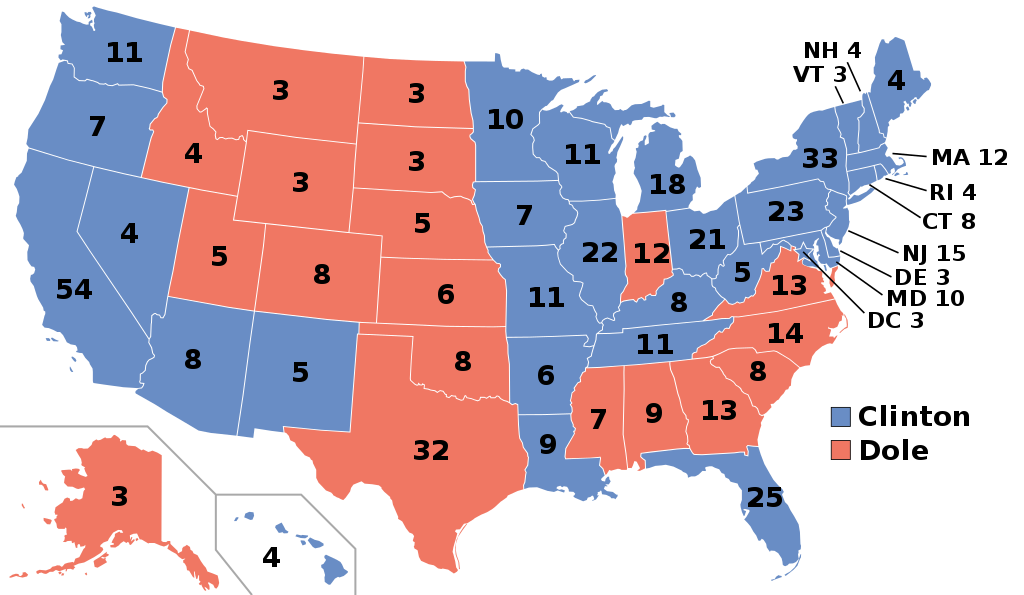

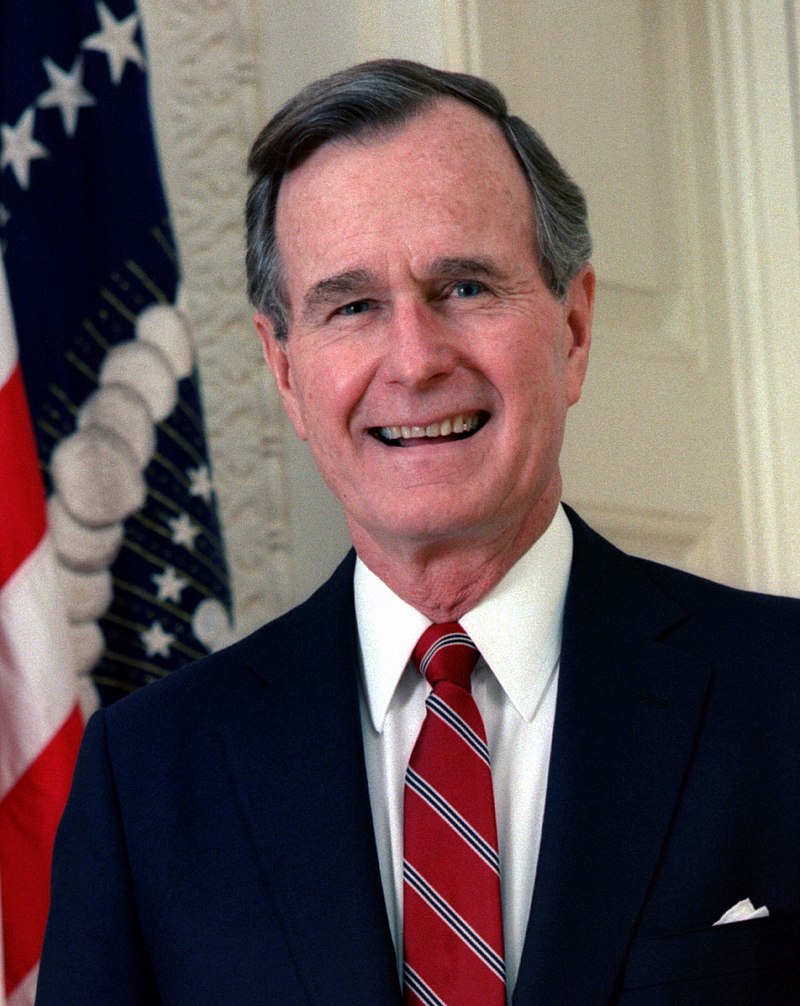

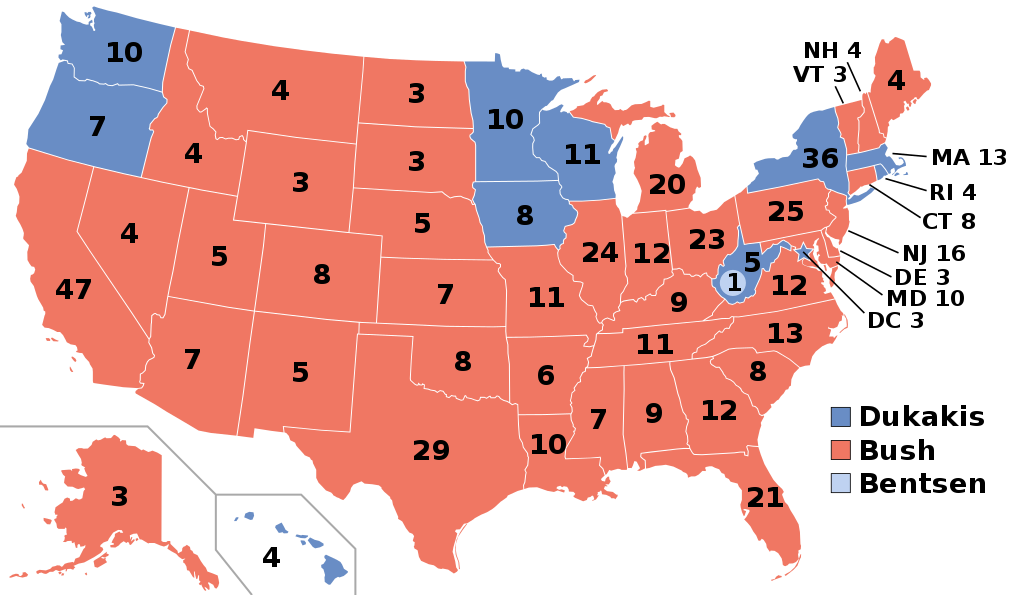

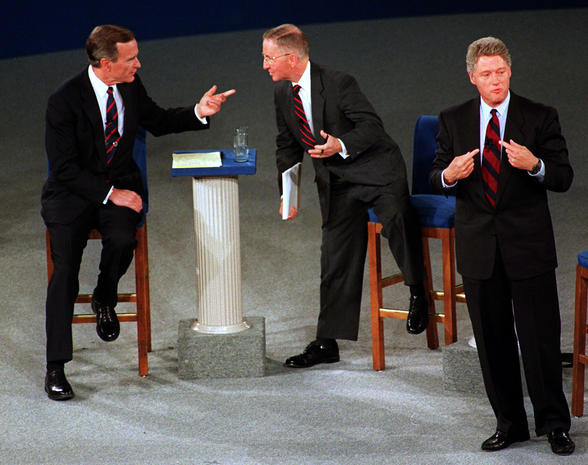

Secondly, there is the issue of viability. No Third Party or Independent candidate has ever won the presidency. However, that is not the point. When Romney cast his vote with the Democrats on Wednesday, he was voting to remove President Trump from office. He clearly believes that the President is unfit for office and must be removed. Following Trump’s acquittal in the Senate, the only method left for removal is the ballot box. Romney’s name on a ballot would no doubt siphon off several million would-be Trump voters across the country. This would increase the likelihood that Trump is removed from office by the voters. Trump no longer occupying the White House would be the result Romney pushed for when he cast his vote on February 5th. Can a minor party candidate have such an impact on a Republican running for re-election? You needn’t look any further than one-term Republican Presidents William Howard Taft and George Bush.

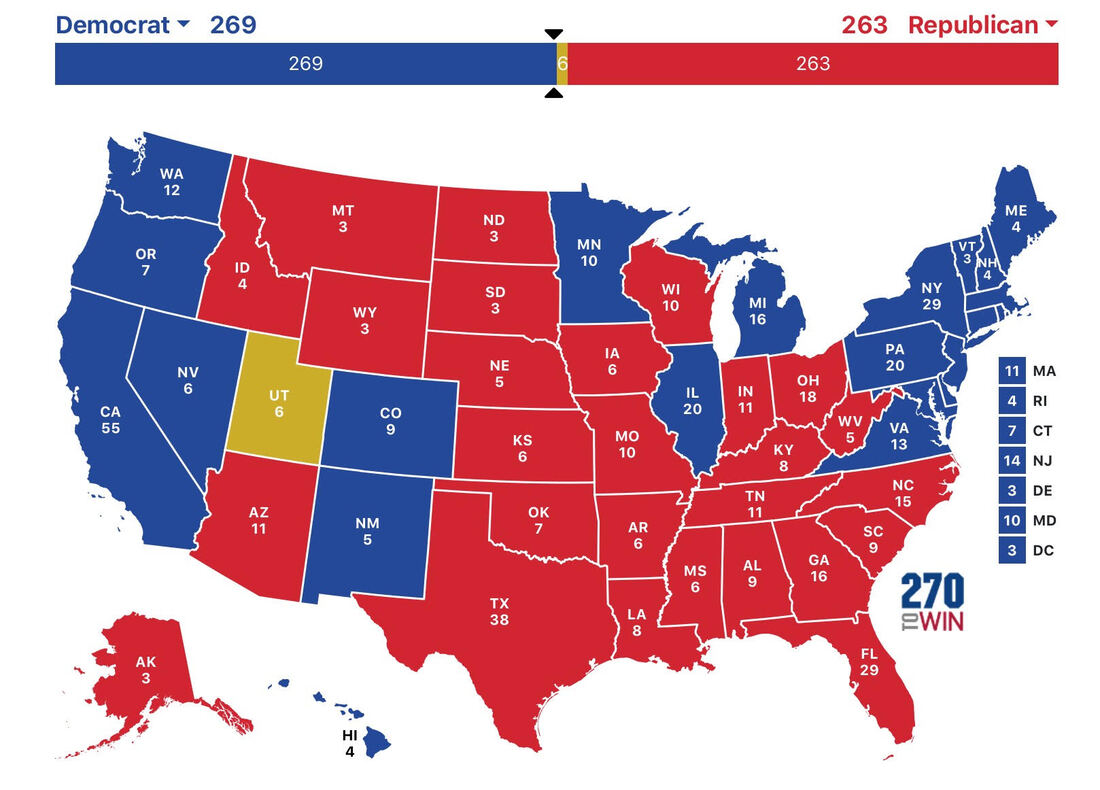

Finally, we must face facts. If Senator Mitt Romney runs for President of the United States as an Independent conservative candidate he...CAN WIN! Yes, he can! There are two reasons for this: math and the Constitution. President Trump doesn’t care much for math (see six bankrupt Trump properties) and he has never had any respect for the Constitution. However, there is one part of the Constitution that Trump loves and the Republican Party will defend until the end: the Electoral College. Mitt Romney can use the Electoral College to deny Trump a second term and potentially win the White House despite coming in a likely third in the popular vote. By winning as little as one traditionally red state, Romney could conceivably prevent either party from winning a majority of the electoral vote (270) thereby sending the election to the House of Representatives as outlined in the Constitution. The House may choose whichever of the top three candidates they wish. This has happened before during the Election of 1824. Could Romney win a single state’s electoral votes? Yes, definitely. His name ID alone would garner him enough media attention to make him be taken seriously and all but guarantee him a spot in the presidential debates. Furthermore, Mitt Romney is uniquely suited to defeat Trump in one state: Utah. Not only is Romney the Senator from Utah, he is a beloved figure in the state. When he ran for president in 2012 he won the state with more than 72% of the vote. By contrast, Trump won deep red Utah by receiving less than 46% of the vote. There is no reason to believe that Mitt Romney could not win Utah. The Electoral Map could look much like the one below with no candidate winning a majority and Romney emerging as the compromise candidate in the House.

If Mitt Romney were to run for President, it would only make sense that he would appear on the ballot in a handful of traditionally red states where he could conceivably win electoral votes and where a successful campaign could be run with limited resources. States like Utah, Idaho, Montana, and Oklahoma would make sense. If resources allow, he could expand his campaign to larger states. If he ran in states such as these there are only 3 outcomes:

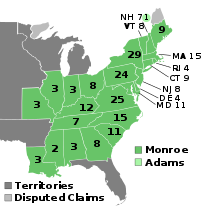

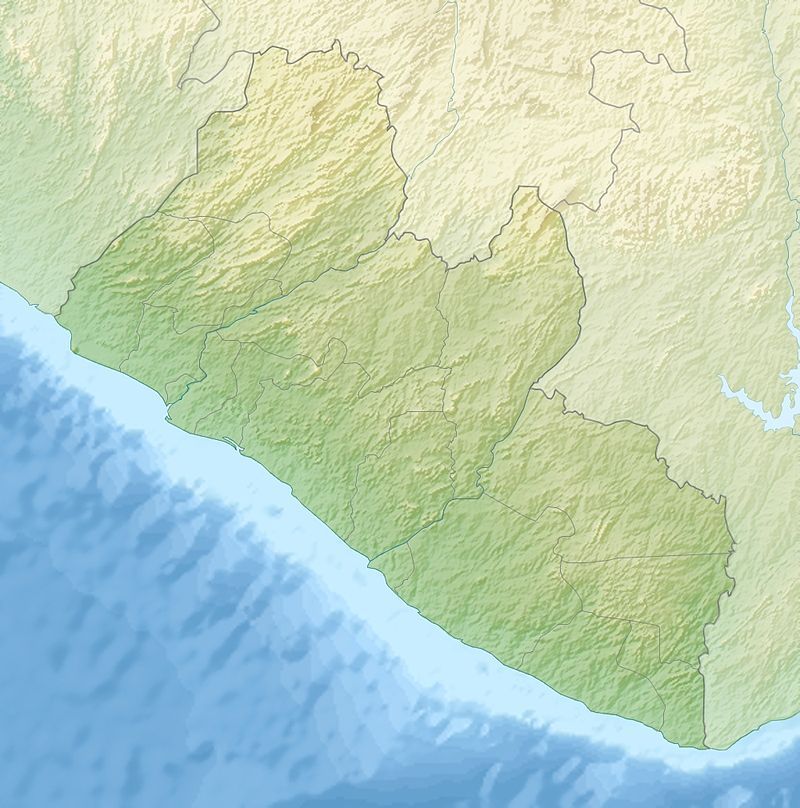

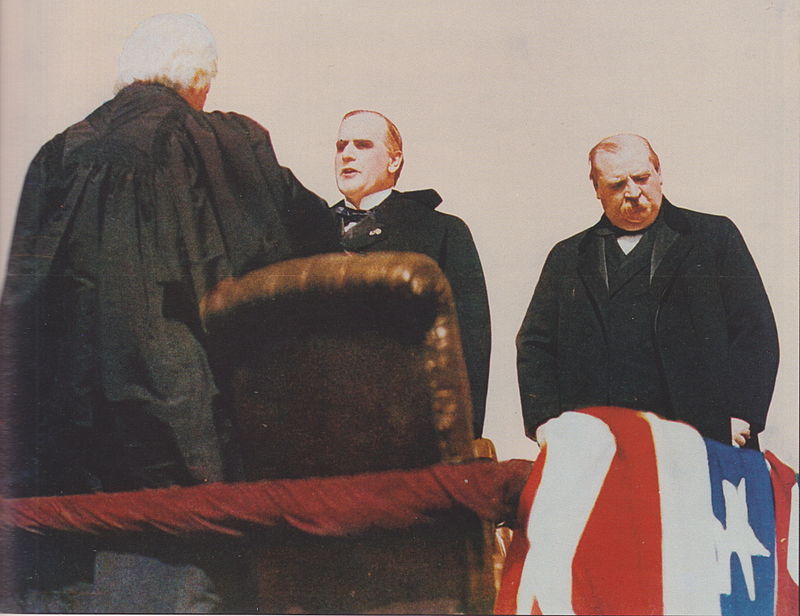

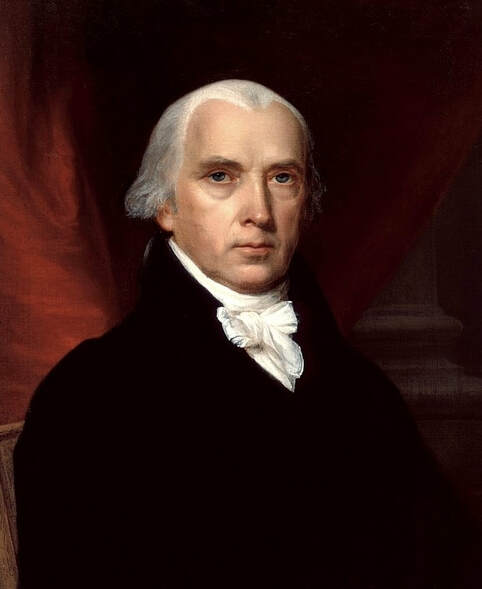

I realize the improbability of such an endeavor. However, Senator Romney took a stand that he can not possibly step away from now. In the eyes of Trump loyalist and the Right Wing media he has committed the cardinal sin: he showed character. He took an oath before God and showed fidelity to our Constitution. This excludes him from ever again being welcome in Donald Trump’s Republican Party. This does not exclude him from standing up for the millions of conservative and moderate voters across the country without a political home. If he chose a running mate such as Rep. Justin Amash, who was kicked out of the GOP for defending the Constitution, Romney would make himself an even more attractive conservative alternative to Trump. With the backing of organizations like The Lincoln Project and the potential endorsements of former Republican leaders like John Kasich, Jeb Bush, and Jeff Flake, Mitt Romney would have a shot. As a Democrat living in a red state where no Democratic presidential candidate stands a realistic chance of winning, I stand ready to support Mitt Romney. I don’t think I'm alone. I did not vote for Mitt Romney in 2012. I have significant disagreements with many of the policies he supports. However, 2020 isn’t about the traditional conservative progressive divide. It is about removing from office a man that poses an existential threat to our Constitution and republic. With his vote on Wednesday, Mitt Romney cast his lot with history and history will be kind. Now it's time for Mitt Romney to lead. “Romney For America” Scott Harris, Executive Director of the James Monroe Museum, likes to compare former president James Monroe to the fictional character Forrest Gump. Much like the titular character portrayed by Tom Hanks in the 1994 film, James Monroe seemed to have a knack for being, almost serendipitously around significant historical events throughout his life. As a young soldier in the American Revolution, Monroe was with Washington as he famously crossed the Delaware River. He is portrayed, inaccurately, as holding the American flag in Washington's boat in the famous painting by Emanuel Leutez, Washington Crossing the Delaware. He later can be seen with a bandaged arm in John Trumbull's iconic The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, After the war, he joined the Continental Congress. During the debate over ratification of the Constitution, Monroe stood with anti-federalists, but was willing to support the Constitution if it was amended to include a Bill of Rights. In the end, his argument carried the day. Early in the new republic, Monroe served as a Senator from Virginia. It was during this time that he, a staunch Democratic-Republican clashed with the leader of the Federalists, Alexander Hamilton. Fans of the Broadway hit Hamilton will be interested to know that, although he isn't a character in the musical, it was Monroe that was tasked with investigating accusations of corruption that would lead to the discovery of the Hamilton-Reynolds Affair immortalized in the songs "We Know" and "The Reynolds Pamphlet". After a few years in the Senate, he was appointed by President Washington to be his ambassador to France. It was at this time that he witnessed the dysfunction and chaos of the French Revolution. His time in France would be the first step in a long and distinguished career as a diplomat. After briefly serving as the Governor of Virginia, Monroe once again went on to serve his nation abroad. President Thomas Jefferson dispatched Monroe to France to settle a growing dispute between France and the United States over access to the Mississippi River. It was at this time that James Monroe would personally negotiate the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the United States. The next year, Monroe was present to witness the coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte as Emperor of France. During the presidency of James Madison, Monroe served as both Secretary of State and Secretary of War at the same time. In 1816, Monroe was the obvious choice to be the Democratic-Republican nominee for president. He won the Election of 1816 in landslide making him the 4th and final member of the so-called Virginia Dynasty that dominated the first 30 years of presidential politics.